Soilless systems are the future of organic

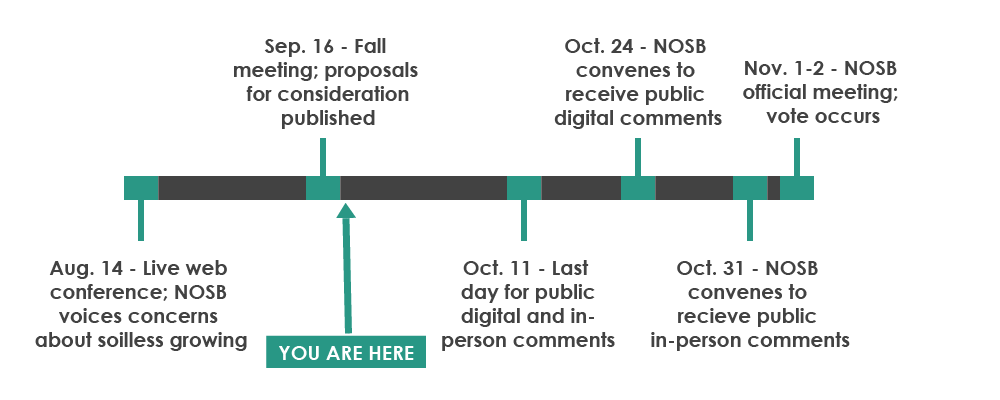

The National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) will vote November 2nd on a prospective rule change that would remove hydroponic, aquaponic, and other soilless or container-based growing systems from the USDA organic label.

This article is part of series in our ongoing coverage about on the NOSB vote. Here’s what we’ve covered so far and what’s to come on the Upstart U blog:

- Top concerns voiced by the NOSB in their live meeting last month.

- How public comments help protect soilless systems’ future

- Why soilless growers and traditional organic growers are on the same side. – Today’s Post

- What happens if soilless systems are banned?

- What happens if soilless growers are given access?

- A response to the recent proposals for the fall NOSB meeting.

- A personal appeal from a certified-organic, soilless grower who will be directly impacted by this vote.

If you’re new to the issue, check out our earlier articles covering the major issues of the vote and recommending action. Today, we’re going to talk about the context surrounding the organic movement and the motivations behind the proposed ban.

Soil wars: What makes organic produce?

A group of extreme “soil only” activists are trying to push soilless production systems out of the organic program. This is despite that fact that organic soilless systems meet the intent of the organic standards and have been certified organic for quite some time.

Miles McEvoy, Deputy Administrator of USDA’s National Organic Program, announced on Monday that he will be stepping down after eight years. In a letter announcing his resignation, McEvoy highlighted that “organic food should be available to everyone from the cities to the countryside…we need all systems and scales of production to transform the agricultural system.”

Soilless methods are an important part of the organic fabric that helps achieve that goal. Our goal at Upstart University is to work together with organic production systems of all shapes and sizes to create an agricultural system that is good for the planet and good for people.

In McEvoy’s words:

“Embracing this diversity of production is critical

as the organic sector grows… We will be much

more successful if we support each other as we confront challenges of water availability and climate change.”

With the aim of embracing this diversity, we’re going to go over a brief history of the organic movement and the formation of the NOSB.

History of the organic movement

The organic movement originated as a loose confederation of farmers and thinkers who were concerned about the risks of the rise in industrial and mechanized agriculture. The NOSB’s 2016 Task Force report writes, “The organic farming movement began in the early part of the twentieth century, pioneered by farmers and academics who were responding to obvious problems with ‘modern’ agriculture such as depletion of soil fertility and structure, decline of livestock health caused by low feed quality, soil erosion, etc.”

Sir Albert Howard was one of the pioneers of the organic movement.

These early organic adopters focused on fostering healthy soil to protect the land that they saw as callously disregarded. Over the next century, these farmers began to share ideas and organize. The 60s and 70s marked the birth of the first organic certification, and in 1990 the Organic Food Production Act (OFPA) was passed. The OFPA marked the birth of what consumers see today as the gold standard of the organic label. The act enabled government regulated certifiers to determine whether organic producers, including farmers, could display the message ‘Meets USDA Organic requirements” on the packaging of their products.

Today, the organic label represents a 50 billion dollar industry. Managing the standards for the massive organic label is no easy task. To take on this challenge, the Organic Food Production Act created a volunteer advisory board, the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), tasked with making recommendations to the USDA’s National Organic Program.

Unfortunately, an extreme minority within the organic community has organized to convince the NOSB to kick soilless production methods out of the program in favor of a “soil only” definition of organic. Organic standards currently allow soilless production methods, and this “soil only” community is trying to make changes to the regulations to keep the organic label for themselves

Diverse methods of organic production can and should continue to exist within the commonly agreed on the definition of “organic”.

The great organic soil debate: Soil vs. soilless

If we had all of our nutrients organic, all of our pesticides and herbicides — whatever we’re doing to control disease was organic, and the medium itself that the roots are growing in is also organic, all the inputs are organic. The outcome, it seems to me, would be organic.”

– Hydroponic farmer Mark Mordasky of Wipple Hydroponic Farms

The above quote frames the question. According to some members of the NOSB, the exclusive focus on just inputs represents a form of organic that only prioritizes the crops – not the soil. These people then make the leap to automatically classify all soilless as input-only organics, even though the input focus is common to both soil as well as soilless growers.

Upstart University growers know that to make soilless production system work, you must actively work to create a stable organic ecosystem that is far more than just adding ingredients to the system.

The “soil only” movement is working hard to convince 10 of the 15 members of the NOSB to side with them to pass a recommendation to eliminate soilless systems by mischaracterizing them as “shallow organic”. They justify this elimination of soilless systems by pointing to a portion of their recommended regulations that state :

“A producer of an organic crop must manage soil fertility including tillage and cultivation practices, in a manner that maintains or improves the physical, chemical, and biological condition of the soil and minimizes soil erosion.”

“Soil used in a container system, with the exception of transplants, shall provide nutrients to plants continuously. The soil (growth media) shall contain a mineral fraction (sand, silt, or clay) and an organic fraction; it shall support life and ecosystem diversity.”

These distinctions are important for growers but impenetrable for the average consumer. The consumer expects the organic label to communicate certain characteristics of the crops and the methods used to grow them.

The reality for organic consumers

Despite the conflict between the different schools of organic farming, the reality is that the consumers who depend and demand the product are unaware of the conflict. We’ve put together a list of qualities that “Organic” is perceived by consumers to mean, and why soilless systems can match these perceptions:

- Production without synthetic chemicals. Indoor and container systems do not require synthetic pesticides or fertilizers. Biological control and other organic methods work extremely well in soilless systems.

Can you spot which produce was grown in soilless systems, and which was grown in traditional farms?

- Production that fosters the cycling of resources, ecological balance, and biodiversity conservation. Soilless systems can be constructed as closed-loop ecosystems in which only the minimum required water and nutrients are added and with minimal or no discharge. Soilless systems have also proven they can produce more food than soil culture per land area, thus saving more of the natural environment from the toll of agriculture and biodiversity loss.

- Production that relies on biological ecosystems to support plant health. Organic soilless production relies on a robust microflora in the root zone—made of the same types and numbers of bacteria and fungi that thrive in soil. This flora converts nutrients into forms available to plants and maintains plant health by reinforcing naturally-occurring mechanisms of disease resistance—just as in a healthy soil.

- Production that responds to site-specific conditions by integrating cultural, biological, and mechanical practices. Consumers expect that organic produce has been grown with a healthy human element, where local customs, expertise, and ingenuity can overcome droughts, concrete jungles, and climate changes. Soilless allow environmentally-sensitive agriculture where growing in soil isn’t possible.

Soilless systems are organic

We submit that hydroponic crops, grown with approved organic inputs and managed without the use of banned pesticides or herbicides, is able to comply with the letter as well as the intent of the organic standard. If organics are going to be available to a diversity of people in both urban and rural environments, a critical piece of the organic production ecosystem will rest in soilless systems.

Let’s preserve Miles McEvoy’s legacy and continue to embrace the diversity of production in organic.

The comment period for the NOSB’s recommendations to the USDA are now closed. To view comments, click here.

Soilless should be organic, if growers can do as organic pratical way. It s look get more advantages than growing in soil. People can consume organic product in suitable price.